It’s not new that Africa being rich in cultures backed by singing and dancing have diversed dance steps all unique to traditional backgrounds and musical tones!

Africans formally divided by colonial influences usually come together via dancing and music!

We dance to songs sang in various languages we may not even understand.

Today we take a trip down memory lane, with a spot light on Africa’s most trending music genres and dance steps from the early 1950’s to present day.

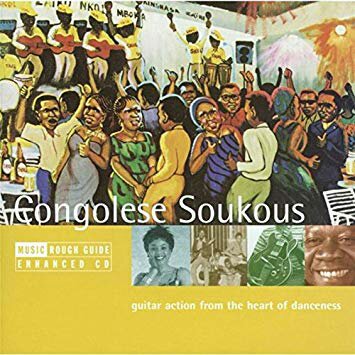

Soukous

Soukous (from French secouer, “to shake”) is a popular genre of dance music from the Congo Basin.It derived from Congolese rumba in the 1960s and gained popularity in the 1980s in France. Although often used by journalists as a synonym for Congolese rumba, both the music and dance currently associated with soukous differ from more traditional rumba, especially in its higher tempo, longer dance sequences. Notable performers of the genre include African Fiesta, Papa Wemba and Pépé Kallé.

In the 1950s and 1960s, some artists who had performed in the bands of Franco Luambo and Grand Kalle formed their own groups. Tabu Ley Rochereauand Dr. Nico Kasanda formed African Fiesta and transformed their music further by fusing Congolese folk music with soul music, as well as Caribbeanand Latin beats and instrumentation. They were joined by Papa Wemba and Sam Mangwana, and classics like Afrika Mokili Mobimba made them one of Africa’s most prominent bands. Congolese “rumba” eventually evolved into soukous. Tabu Ley Rochereau and Dr Nico Kasanda are considered the pioneers of modern soukous. Other greats of this period include Koffi Olomide, Tshala Muana and Wenge Musica.

While the rumba influenced bands such as Lipua-Lipua, Veve, TP OK Jazz and Bella Bella, younger Congolese musicians looked for ways to reduce that influence and play a faster paced soukous inspired by rock n roll. A group of students called Zaiko Langa Langa came together in 1969 around founding vocalist Papa Wemba. Pepe Kalle, a protégé of Grand Kalle, created the band Empire Bakuba together with Papy Tex and they too became popular.

East Africa in the 1970

Soukous now spread across Africa and became an influence on virtually all the styles of modern African popular music including highlife, palm-wine music, taarab and makossa. As political conditions in Zaire, as the Democratic Republic of Congo was known then, deteriorated in the 1970s, some groups made their way to Tanzania and Kenya. By the mid-seventies, several Congolese groups were playing soukous at Kenyan night clubs. The lively cavacha, a dance craze that swept East and Central Africa during the seventies, was popularized through recordings of bands such as Zaiko Langa Langa and Orchestra Shama Shama, influencing Kenyan musicians. This rhythm, played on the snare drum or hi-hat, quickly became a hallmark of the Congolese sound in Nairobi and is frequently used by many of the regional bands. Several of Nairobi’s renowned Swahili rumba bands formed around Tanzanian groups like Simba Wanyika and their offshoots, Les Wanyika and Super Wanyika Stars.

In the late 1970s

Virgin records produced LPs from the Tanzanian-Congolese Orchestra Makassy and the Kenya-based Super Mazembe. One of the tracks from this album was the Swahili song Shauri Yako (“it’s your problem”), which became a hit in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. Les Mangelepa was another influential Congolese group that moved to Kenya and became extremely popular throughout East Africa. About this same time, the Nairobi-based Congolese vocalist Samba Mapangala and his band Orchestra Virunga, released the LP Malako, which became one of the pioneering releases of the newly emerging world music scene in Europe. The musical style of the East Africa-based Congolese bands gradually incorporated new elements, including Kenyan benga music, and spawned what is sometimes called the “Swahili sound” or “Congolese sound”.

1980s and the Paris scene

Soukous became popular in London and Paris in the 1980s. A few more musicians left Kinshasa to work around central and east Africa before settling in either the UK or France. The basic line-up for a soukous band included three or four guitars, bass guitar, drums, bass, vocals, and some of them having over 20 musicians. Lyrics were often in Lingala and occasionally in French. In the late 1980s and 1990s, Parisian studios were used by many soukous stars, and the music became heavily reliant on synthesizers and other electronic instruments. Some artists continued to record for the Congolese market, but others abandoned the demands of the Kinshasa public and set out to pursue new audiences. Some, like Paris-based Papa Wemba maintained two bands, Viva La Musica for soukous, and a group including French session players for international pop.

Kanda Bongo Man, another Paris-based artist, pioneered fast, short tracks suitable for play on dance floors everywhere and popularly known as kwassa kwassa after the dance moves popularized by his and other artists’ music videos. This music appealed to Africans and to new audiences as well. Artists like Diblo Dibala, Jeannot Bel Musumbu, Mbilia Bel, Yondo Sister, Tinderwet, Loketo, Rigo Star, Madilu System, Soukous Stars and veterans like Pepe Kalleand Koffi Olomide followed suit. Soon Paris became home to talented studio musicians who recorded for the African and Caribbean markets and filled out bands for occasional tours.

In the 1980s, the fast tempo zouk style popularized by the French Antilles band Kassav’ became popular across much of Paris and French Africa. In the 1980s and early 1990s, a fast-paced style of soukous known as kwassa kwassa, named after a popular dance, was popular. Today, soukous mixes the kwasa kwasa with zouk and Congolese rumba. A style called ndombolo, also named after a dance, is currently popular.

Ndombolo

The fast soukous music currently dominating dance floors in central, eastern and western Africa is called soukous ndombolo, performed by Dany Engobo, Awilo Longomba, Aurlus Mabele, Mav Cacharel, Koffi Olomide and groups like Extra Musica and Wenge Musica among others.

The hip-swinging dance of the fast paced soukous ndombolo has come under criticism on claims that it is obscene. There have been attempts to ban it in Mali, Cameroon and Kenya. After an attempt to ban it from state radio and television in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2000, it became even more popular. In February 2005, ndombolo music videos in the DR Congo were censored for indecency, and video clips by Koffi Olomide, JB M’Piana and Werrason were banned from the airwaves.

Makossa

While the Congolese brought us Soukous, Cameroonians more precisely the Sawa tribe dazeled us with makossa in a language we all sang but just a few understand.

Makossa is a noted Cameroonian popular urban musical style. Like much other late 20th century music of Sub-Saharan Africa, it uses strong electric bass rhythms and prominent brass. In the 1980s makossa had a wave of mainstream success across Africa and to a lesser extent abroad.

Makossa, which means “(I) dance” in the Douala language, originated from a Douala dance called the kossa. Emmanuel Nelle Eyoum started using the refrain kossa kossa in his songs with his group Los Calvinos. The style began to take shape in the 1950s though the first recordings were not seen until a decade later. There were artists such as Eboa Lotin, Misse Ngoh and especially Manu Dibango, who popularised makossa throughout the world with his song “Soul Makossa” in the early 1970s. The chant from the song, mamako, mamasa, maka makossa, was later used by Michael Jackson in “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin’“. Many other performers followed suit. The 2010 World cup also brought makossa to the international stage as Shakira sampled the Golden Sounds popular song “Zamina mina (Zangalewa)“.

Makassi is a lighter style of makossa.

Later in the 1960s, modern makossa developed and became the most popular genre in Cameroon. Makossa is a type of funky dance music, best-known outside Africa for Manu Dibango, whose 1972 single “Soul Makossa” was an international hit. Outside of Africa, Dibango and makossa were only briefly popular, but the genre has produced several pan-African superstars through the 70s, 80s and 90s. Following Dibango, a wave of musicians electrified makossa in an attempt at making it more accessible outside of Cameroon. Another pop singer in 1970s Cameroon was André-Marie Tala, a blind singer who had a pair of hits with “Sikati” and “Potaksima”.

By the 1970s, bikutsi performers like Maurice Elanga, Les Veterans and Mbarga Soukous added brass instruments and found controversy over pornographic lyrics. Mama Ohandja also brought bikutsi to new audiences, especially in Europe. The following decade, however, saw Les Tetes Brulées surpass previous artists in international popularity, though their reaction at home was mixed. Many listeners did not like their mellow, almost easy listening-styled bikutsi. Cameroonian audiences preferred more roots-based performers like Jimmy Mvondo Mvelé and Uta Bella, both from Yaoundé.

By the 1980s, makossa had moved to Paris and formed a new pop-makossathat fused the fast tempo zouk style popularized by Kassav from the French Caribbean. Prominent musicians from this period included Moni Bilé, Douleur, Bébé Manga, Ben Decca, Petit-Pays, and Esa.

The 80s also saw rapid development of Cameroon’s media which saw a flourishing of both makossa and bikutsi. In 1980, L’Equipe Nationale de Makossa was formed, joining the biggest makossa stars of the period together, including Grace Decca, Ndedi Eyango, Ben Decca, Guy Lobe and Dina Bell. Makossa in the 80s saw a wave of mainstream success across Africa and, to a lesser degree, abroad, as Latin influences, French Antilles zouk, and pop music changed its form. While makossa enjoyed international renown, bikutsi was often denigrated as the music of savages and it did not appeal across ethnic lines and into urban areas. Musicians continued to add innovations, however, and improved recording techniques; Nkondo Si Tony, for example, added keyboards and synthesizers, while Elanga Maurice added brass instruments.Les Veterans emerged as the most famous bikutsi group in the 80s, while other prominent performers included Titans de Sangmelima, Seba Georges, Ange Ebogo Emerent, Otheo and Mekongo President, who added complex harmonies and jazz influences.

In 1984, a new wave of bikutsi artists emerged, including Sala Bekono formerly of Los Camaroes, Atebass, a bassist, and Zanzibar, a guitarist who would eventually help form Les Têtes Brulées with Jean-Marie Ahanda. 1985 saw the formation of Cameroon Radio Television, a television network that did much to help popularize Cameroonian popular music across the country.

Jean-Marie Ahanda became the most influential bikutsi performer of the late 80s, and he revolutionized the genre in 1987 after forming Les Têtes Brulées, whose success changed the Cameroonian music industry. The band played an extremely popular form of bikutsi that allowed for greater depth and diversity. Guitarist Zanzibar added foam rubber to the bridge of his guitar, which made the instrument sound more like a balafon than before, and was more aggressive and innovative than previous musicians. Les Têtes Brulées emerged as a reaction against pop-makossa, which was seen as abandoning its roots in favor of mainstream success. The band’s image was part of its success, and they became known for their shaved heads and multi-colored body painting, done to represent traditional Beti scarification, as well as torn T-shirts that implied a common folkness in contrast to the well-styled pop-makossa performers of the period. They also wore backpacks on stage, a reference to Beti women’s traditional method of carrying babies while they danced bikutsi.

It took only a few weeks for Les Têtes Brulées to knock makossa off the Cameroonian charts, and the band even toured France. While in France, Les Têtes Brulées recorded their first LP, Hot Heads, which was also the first bikutsi music recorded for the CD. Hot Heads expanded the lyrical format of the genre to include socio-political issues. Tours of Japan, Africa, Europe and the United States followed, as well as Claire Denis‘ film Man No Run, which used footage from their European tour.

.

In the 1990s, both makossa and bikutsi declined in popularity as a new wave of genres entered mainstream audiences. These included Congolese-influenced new rumba and makossa-soukous, as well as more native forms like bantowbol, northern Cameroonian nganja (which had gained some popularity in the United Kingdom in the mid-80s) and an urban street music called bend-skin.

Les Têtes Brulées remained the country’s most well known musical export, especially after accompanying the Cameroonian soccer team to the World Cupin 1990 in Italy and 1994 in the United States. A new wave of bikutsi artists arose in the early 1990s, including Les Martiens (formed by Les Têtes Brulées bassist Atebass) and the sexually themed roots singer Katino Ateba(“Ascenseur: le secret de l’homme”) and Douala singer Sissi Dipoko (“Bikut-si Hit”) as well as a resurgence of old performers like Sala Bekono. Bikutsi’s international renown continued to grow, and the song “Proof” from Paul Simon‘s Rhythm of the Saints, released to mainstream promotion and success in 1990, gained yet more renown from international audiences. Vincent Nguini also contributed guitar arrangements and performance to Simon’s Rhythm of the Saints, which became an influential world music album, introducing many North American listeners to the wide range of instrumentation and genres.

In 1993, the Pedalé movement was born as a reaction to the Cameroonian economic slump. Youthful artists like Gibraltar Drakuss, Zele le Bombardier, Eboue Chaleur, Pasto, Roger Bekono, Mbarga Soukous and Saint-Desiré Atangowas a return to the aggressive, earthy sound of bikutsi roots. Meanwhile Henri Dikongué, whose music incorporated, amongst others, bikutsi and makossa, began to release albums which met international success. He went on to tour Europe and North America. The most recent form of Cameroonian popular music is a fusion of Congolese soukous and makossa, a scene which has produced Petit Pays, Marcel Bwanga, Kotto Bass, Papillon and Jean Pierre Essome.

Coupé-Décalé

Then came ivory coast with a new sound unheard before branded and exported almost instantly to the world.

Coupé-Décalé is a type of popular dance music originating from Côte d’Ivoireand the Ivorian diaspora in Paris, France. Drawing heavily from Zouglou and Zouk with African influences, Coupé-Décalé is a very percussive style featuring African samples, deep bass, and repetitive minimalist arrangements.

While Coupé-Décalé is known as Côte d’Ivoire’s definitive pop music, it actually began in Paris, created by a group of Ivorian DJs at the Atlantis, an African nightclub in northeast Paris. These Djs, known as the ‘Jet Set’, became popular for their flamboyant style, often showing up at the club with large amounts of cash which they would hand out to audiences on the dance floor. Their aesthetic defined the early sounds of Coupé Décalé, apparent in the genre’s name. In Nouchi (Ivorian slang), Coupé means “to cheat” and Décalé means to “run away”, so Coupé-Décalé basically means to cheat somebody and run away. The ‘somebody’ cheated is generally interpreted to mean France or the West/Europe, finding parallels to the idea of “The Man” in American culture. Especially in the beginning, the songs often celebrated those who had used guile to ‘make it’ abroad. The word boucantier (English: “shoe-maker”) was applied to performers with unusual style, as well as to their imitators.

The genre’s first hit, “Sagacité” was pioneered by the late Stephane Doukouré (a.k.a. “Douk-Saga”), a member of the ‘Jet Set’, during the post-2002 militaro-political crisis in Côte d’Ivoire. The hit became a success in African clubs in Paris and spread quickly among disc jockeys in Côte d’Ivoire. According to Siddhartha Mitter of Afropop,

“[Coupé-Décalé ] has become very popular at a time of conflict; in fact, Ivorian music has really for the first time taken over dance floors all over Africa at exactly the same time that Ivory Coast, the country, has been going through this protracted political and military crisis, with debilitating social and economic effects”.

Although arising from this time of political turmoil, Coupé-Décalé lyrically addresses topics such as relationships, earning money and maintaining a good mood or ‘bonne ambiance’. Much of its lyrics refer to specific dance moves, often referencing current events such as the avian flu dance or Guantanamo(with hand movements imitating hands raised in chains). These global themes could have helped to make Coupé-Décalé so deeply popular across a politically divided Côte d’Ivoire and spread its influence so far across Africa and the diaspora. Increasingly non-Ivorian artists, particularly in the Congo, are beginning to play and incorporate the musical style. Notably among these artists are Congolese Djouna “Big One” Mumbafu and French/Malian rapper Mokobe with “Bisous” feat. Dj Lewis and “On Est Ensemble” feat. Molare. Even outside of African and its diaspora, there has been a growing interest in coupé décalé. In February 2009, Akwaaba Music released an Ivorian and Ghanaian compilation, one of the first legal worldwide releases of coupé décalé, highlighting some of the recent coupé décalé released in Côte d’Ivoire. The compilation features music by DJ Menza, DJ Bonano, DJ Mix 1er & Eloh DJ and Kedjevara.

Movements within Coupé-Décalé

Georges Dyoula has distinguished 3 waves in the development of Coupé-Décalé, with us currently being in the 3rd wave:

1st wave, ~2002–2004 : The appearance, success and domination of the JetSet, Dj Allan, Dj Arafat, Dj Jacob, Dj Serpent Noir, Bloco, Ericks ok 9on le Zulu, Dj String, Dj Ressource, Shégal Mokonzi, Mama Ministre, Youlés Inter, Dj Jeff, Ayano…2nd wave, 2005–2006 : This period is essentially led by « la danse de la Moto » and dances relating to football (Konami, Drogbacité, Kolocité,…). The appearance, success and domination of Boulevard Dj, Dj Rodrigue, Shanaka Yakusa, Danny Blue Dj, Dj Gaoussou, Oxxy Norgy, Roland Le Binguiss, Douk Saga, Christina DJ, Le Molare, Solo Béton, Erickson le Zulu, Dj Zidane, Ligue Dj, Dj Disconty, Kilabongo, PS One Dj,…3rd wave – 2006–2010 : The 3rd wave includes the most new artists and new derivative styles of dance. This wave is also associated with a ‘Congolization’ of rhythms, lyrics and artists. The appearance, success and domination of Dj Lewis, Dj Bonano, Dj Roi Lion, Francky Dicaprio, Dj Mix, Elloh Dj, Dj Phéno, Mustapha Al Kabila, Mareshal Dj, Harmony, Maty Dollar, Linda de Lindsay, Ronaldo R9, Dj TV3, Debordeaux Dj, Erickson le Zulu, Dollar-R, Miki Dollar, TPJ New Version, Jean-jacques Kouamé, Abou Nidal…4th wave – 2011–present :Mainly led by former artists such as Meiway and other known artists, Abson Kabyla, Papa Fololo, Kedjevara DJ, DJ Arafat

In 2005, Vladimir Cagnolari suggests that the music is a way Ivorians are coping with their unstable political situation.

“For a few hours, the rooms is transformed into an ephemeral temple of festival/party, using carefreeness and amusement to counter the socio-political problems of a country still waiting for peace. … In a musical landscape dominated by patriotic and military music, coupé-décalé arrives like a breath of fresh air to forget the difficult context in which Ivorians are living.”

In 2006, Dominik Kohlhagen wrote:

“Over the past three years, Coupé-Décalé has become one of the most thriving forms of popular music in francophone Africa. Produced by people who claim to have achieved “success” abroad, Coupé-Décalé represents “elsewhere” as a site from which one can achieve a certain status in consumer society so as to return home to be celebrated. This music expresses generationel transformations that affect lifestyles in Africa as well as ways of projecting oneself in the world.”

The prominent artists of Coupé-Décalé are Douk-Saga (Doukouré) with its Jet Set, DJ Brico, DJ Arsenal, Papa Ministre with his famous tune “Coupé-Décalé Chinois”, David Tayorault, Afrika Reprezenta, and many other talented Ivorian artists. DJ Lewis is a particularly notable singer, famous for his Grippe Aviaire Dance (en: avian flu dance)nick princy le president.

In 2005, Jessy Matador decided to create his own group called “La Sélésao” composed of members Dr.Love, Linho and Benkoff. The same members also formed the first edition of the group Magic System. In late 2007, they signed with Oyas Records before signing with Wagram Records in spring 2008. They released their début single “Décalé Gwada” in June 2008, becoming one of the hits of that summer. On 24 November 2008 the group released the album Afrikan New Style, a musical hybrid of African and Caribbean influences with more urban sounds. The style includes influences of zouk, dancehall, reggae, hip hop, Coupé-Décalé, ndombolo and kuduro. In June 2013, an upbeat dance song was released on YouTube by Minjin titled “Coupé-Décalé” It featured Iyanya, a Nigerian artist famous for his hit single “Kukere”.

From Coupé Decalé, our Nigerian brothers couldn’t just keep calm after dancing to imported music from Congo, Cameroon and Ivory Coast, being a music giant themselves had to come up with something modern from their rich background of Music!

Leading to distinct tracks from now legends like 2 face idebia, Timaya, P-square.

Not to forget the dance moves that came along such as the alanta, Shuki, Skelewu, just to name a few!.

To our present day, the Nigerians still top the chart with trending dance moves and unique afrobeats from artist like Olamide, Yemi Alade and co who brought fought Ghanians to mimic same trends and boost their popularity across the globe!

Coupé Decalé still very much active spreading to other countries such as Togo, Mali; with groups such as Toofan which bring fought a new dance with almost every song such as Gweta, Téré and many more.

Our Cameroonian Artist on the other hand make extremely catchy songs but lack the vibe of a dance step to accompany our rythemes.

The last we heard was from Franko in Collé la Petit

Could this be due to a disconnection between musicians and dancers?

Could this be because the dancers have limited camera time on music videos?

Could their limited Camera time be due to unoriginal dance moves?

If we are going to keep the wave of African Music going, we need to develop trending dance moves that relate to our African Music and make sure this moves are put on screen and promoted by the right people no matter how ridiculous it may seem at the start, it’s gonna catch on!

LET’S GET EXTRA CREATIVE.